“Hrant Dink remains a potent symbol of the struggle against colonialism, genocide, and racism.”

Those are the words of Angela Davis, renowned scholar, activist and Black civil rights icon. Now a professor emerita at the University of California Santa Cruz, Davis has re-emerged as a leading voice in the era of a burgeoning civil rights movement spurred on by the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer, calling the now global moment “extraordinary” and different to anything she’s experienced in the past.

Back in 2015 however, on the centennial of the Armenian Genocide, Davis was invited to deliver the Hrant Dink Memorial Lecture at Boğaziçi University in Istanbul as part of an annual conference established in 2008 to remember and honor the legacy of Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink, who was assassinated on Jan. 19, 2007.

The conference, in its eighth year at the time, has invited leading figures to deliver keynotes, including Indian author Arundhati Roy, social activist Naomi Klein and Armenian-American professor Ronald. G. Suny, whose book "They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else": A History of the Armenian Genocide,” was published in 2015.

Dink, born in Malatya, Turkey, gravitated towards leftists politics and activism as a young man in the radical 1960s, and changed his name to "Firat" after worrying his activities could be linked back to his heritage and harm Armenians living in Turkey.

He was the founding editor of the pioneering bilingual Armenian-Turkish newspaper Agos, and like Davis, an advocate for the advancement of human rights, free speech, and liberation. Agos was the first weekly newspaper to be published in Istanbul in both Armenian and Turkish, with the aim of opening up debate, dialogue and transparency about the Turkish-Armenian community and diaspora at large, as well as the relationship of Turkey on both a social and state level with its Armenian and minority populations, including issues of identity and the events of 1915.

Dink was prosecuted several times for “insulting Turkishness” and received death threats from Turkish nationalists who portrayed him as an enemy of Turkey before he was murdered in front of the Agos offices in broad daylight. The killing sparked international outrage as well as protests in Turkey - becoming a “symbol of the racism and ultranationalism grinding at the core of Turkish society, a wary against freedom of expression, and the complacency of Turkey’s intellectuals,” according to the New Yorker.

Davis, born in Birmingham, became an activist at an early age, spurred on by experiences growing up in Alabama. Her family lived in a neighborhood known as “Dynamite Hill,” where bombings of houses occured by the Klu Klux Klan to drive out and intimidate Black families who had moved there. Davis personally knew three of the four girls killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, a white supremacist terrorist attack where dynamite was planted beneath the steps of the church.

She studied at the University of Frankfurt in Germany before earning a doctorate of philosophy upon her return to the U.S. Davis was put on the FBI’s most wanted list and spent over a year in jail in connection with the Marin County Civic Center Attacks in 1970. She was acquitted in 1972.

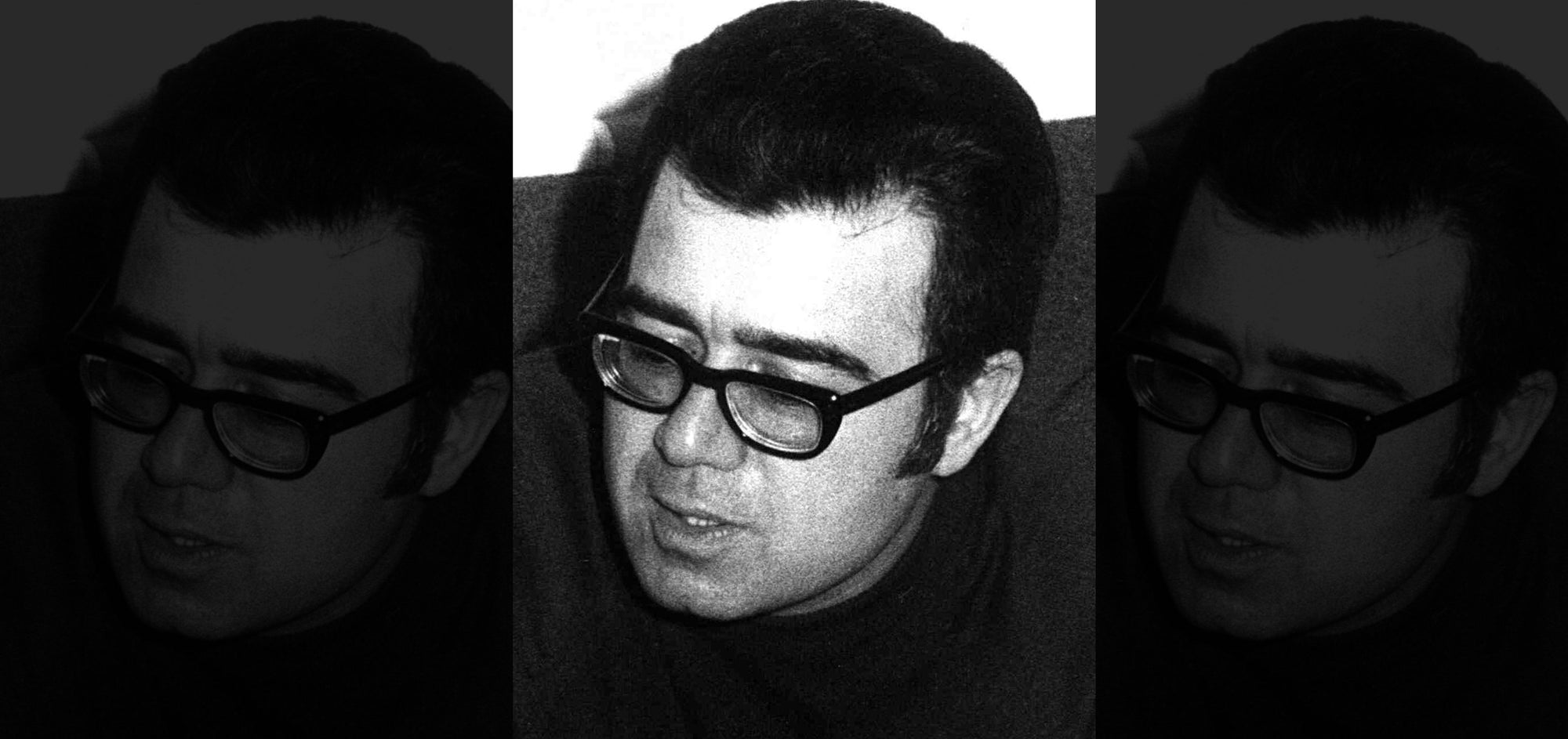

Angela Davis speaking at a street rally in 1974

“As far as Angela Davis is concerned, I said may she long live in liberty and I mean that,” Charles R. Garry, the Armenian-American civil rights lawyer best known for representing the Black Panther Party once said.

In addition to commemorating Dink’s historic work, the memorial lecture is meant to be a reminder of the “resonances between that work and local struggles for equality and social justice throughout the world.”

Davis spoke of her relationship to Turkey, Hrant Dink’s legacy, the genocide, racial injustice, and how wanting to evoke interconnected futures and movements across the world, specifically between the U.S., Turkey and Palestine led to titling her Hrant Dink memorial lecture, “Transnational Solidarities: Resisting Racism, Genocide, and Settler Colonialism.”

“Don’t we want to be able to imagine the expansion of freedom and justice in the world, as Hrant Dink urged us to do—in Turkey, in Palestine, in South Africa, in Germany, in Colombia, in Brazil, in the Philippines, in the US?” she told the large crowd at Boğaziçi University in 2015.

The following condensed excerpts are from Davis’s talk, which can be found in full in her 2015 book of essays, “Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement,” a collection that is topping recommended reading lists in the wake of the George Floyd protests.

On Hrant Dink

"Those who assume that it was possible to eradicate his dream of justice, peace, and equality must now know that by striking him down countless Hrant Dinks were created, as people all over the world exclaim, “I am Hrant Dink.” We know that his struggle for justice and equality lives on. Ongoing efforts to create a popular intellectual environment within which to explore the contemporary impact of the Armenian genocide are central, I think, to global resistance to racism, genocide, and settler colonialism.

The spirit of Hrant Dink lives on and grows stronger and stronger. I am very pleased that I’ve been accorded the opportunity to join a very long list of distinguished speakers who have paid tribute to Hrant Dink."

Hrant Dink demonstation, Istanbul

On the Intersection of the Armenian Genocide and Racial Injustice in America

"The term “genocide” has usually been reserved for particular conditions defined in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, which was adopted on December 9, 1948, in the aftermath of the fascist scourge during World War II. Some of you are probably familiar with the wording of that convention, but let me share it with you: “Any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group as such, killing members of the group, causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group, deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part, imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group, and forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

This convention was passed in 1948, but it was not ratified by the US until 1987, almost forty years later. However, just three years after the passage of the convention, a petition was submitted to the United Nations by the Civil Rights Congress of the US, charging genocide with respect to Black people in the US...

In the introduction to this petition, one can read the following words: “Out of the inhuman Black ghettos of American cities, out of the cotton plantations of the South, comes this record of mass slayings on the basis of race, of lives deliberately warped and distorted by the willful creation of conditions making for premature death, poverty, and disease. It is a record that calls aloud for condemnation, for an end to these terrible injustices that constitute a daily and ever-increasing violation of the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.”

The introduction continues, “We maintain, therefore, that the oppressed Negro citizens of the United States, segregated, discriminated against, and long the target of violence, suffer from genocide as the result of the consistent, conscious, unified policies of every branch of government.”

I mention this historic petition against genocide first because such a charge could have also been launched at the time based on the mass slaughters of Armenians, the death marches, the theft of children and the attempt to assimilate them into dominant culture."

On Fethiye Çetin’s book, “My Grandmother: An Armenian Turkish Memoir,” which explores a hidden family secret about her Armenian roots; and slavery

"I had the opportunity to read the very moving memoir "My Grandmother, an Armenian Turkish memoir" by Fethiye Çetin. I’m certain everyone in this room has read the book. I also learned that as many as two million Turks might have at least one grandparent of Armenian heritage, and that because of prevailing racism, so many people have been prevented from exploring their own family histories. Reading “My Grandmother,” I thought about the work of a French Marxist anthropologist whose name is Claude Meillassoux. This imposed silence with respect to ancestry reminded me that his definition of slavery has the concept of social death at its core. He defined the slave as subject to a kind of social death —the slave as a person who was not born, non née. Of course, there’s grave collective psychic damage that is a consequence of not being acknowledged within the context of one’s ancestry.

Those of us of African descent in the US of my age are familiar with that sense of not being able to trace our ancestry beyond, as in my case, one grandmother. Deprivation of ancestry affects the present and the future. Of course, “My Grandmother” details the process of ethnic cleansing, the death march, the killings by the gendarmes, the fact that when they were crossing a bridge, the grandmother’s own grandmother threw two of her grandchildren in the water and made sure they had drowned before she threw herself into the water. And for me the scene so resonated with historical descriptions of slave mothers in the US who killed their children in order to spare them the violence of slavery."

On Turkey Confronting Its History of Genocide

"Our histories never unfold in isolation. We cannot truly tell what we consider to be our own histories without knowing the other stories. And often we discover that those other stories are actually our own stories. This is the admonition “Learn your sisters’ stories” by Black feminist sociologist Jacqui Alexander. This is a dialectical process that requires us to constantly retell our stories, to revise them and retell them and relaunch them. We can thus not pretend that we do not know about the conjunctures of race and class and ethnicity and nationality and sexuality and ability.

I cannot prescribe how you come to grips with the imperial past of this country. But I do know, because I have learned this from Hrant Dink, from Fethiye Çetin, and others, that it has to be possible to speak freely, it has to be possible to engage in free speech. The ethnic-cleansing processes, including the so-called population exchanges at the end of the Ottoman Empire that inflicted incalculable forms of violence on so many populations—Greeks and Syrians, and, of course, Armenians—have to be acknowledged in the historical record. But popular conversations about these events and about the histories of the Kurdish people in this space have to occur before any real social transformation can be imagined, much less rendered possible."

Armenians at the Marash army barracks awaiting execution. Above them stand the Ottoman governor, Haydar Pasha, and soldiers, April 1915. Photograph: Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute.

On Transnational Solidarities

"The greatest challenge facing us as we attempt to forge international solidarities and connections across national borders is an understanding of what feminists often call “intersectionality.” Not so much intersectionality of identities, but intersectionality of struggles. Let us not forget the impact of Tahrir Square and the Occupy movement all over the world. And since we are gathered here in Istanbul, let us not forget the Taksim Gezi Park protesters.

When we think about the impact of these imaginative and innovative actions and these moments where people learned how to be together without the scaffolding of the state, when they learned to solve problems without succumbing to the impulse of calling the police, that should serve as a true inspiration for the work that we will do in the future to build these transnational solidarities. Don’t we want to be able to imagine the expansion of freedom and justice in the world, as Hrant Dink urged us to do—in Turkey, in Palestine, in South Africa, in Germany, in Colombia, in Brazil, in the Philippines, in the US? If this is the case, we will have to do something quite extraordinary: We will have to go to great lengths. We cannot go on as usual. We cannot pivot the center. We cannot be moderate. We will have to be willing to stand up and say no with our combined spirits, our collective intellects, and our many bodies."

On Being Remembered:

"Often people ask me how I would like to be remembered. My response is that I really am not that concerned about ways in which people might remember me personally. What I do want people to remember is the fact that the movement around the demand for my freedom was victorious. It was a victory against insurmountable odds, even though I was innocent; the assumption was that the power of those forces in the US was so strong that I would either end up in the gas chamber or that I would spend the rest of my life behind bars. Thanks to the movement, I am here with you today."

Hrant Dink Memorial Lecture 2015 - Angela Davis from Boğaziçi Üniversitesi on Vimeo.

1 comment

James R. Roesch

Angela Davis, noted for her activism to abolish prisons in the U.S.A., was an apologist for the prison system in the U.S.S.R. Whenever I think about her, I think about how Stalin backed Communism among black people in the U.S.A., planning to create a separatist movement which would undermine his Cold-War nemesis. (That was before her time, of course, but she’d make Uncle Joe proud.)

Angela Davis, noted for her activism to abolish prisons in the U.S.A., was an apologist for the prison system in the U.S.S.R. Whenever I think about her, I think about how Stalin backed Communism among black people in the U.S.A., planning to create a separatist movement which would undermine his Cold-War nemesis. (That was before her time, of course, but she’d make Uncle Joe proud.)