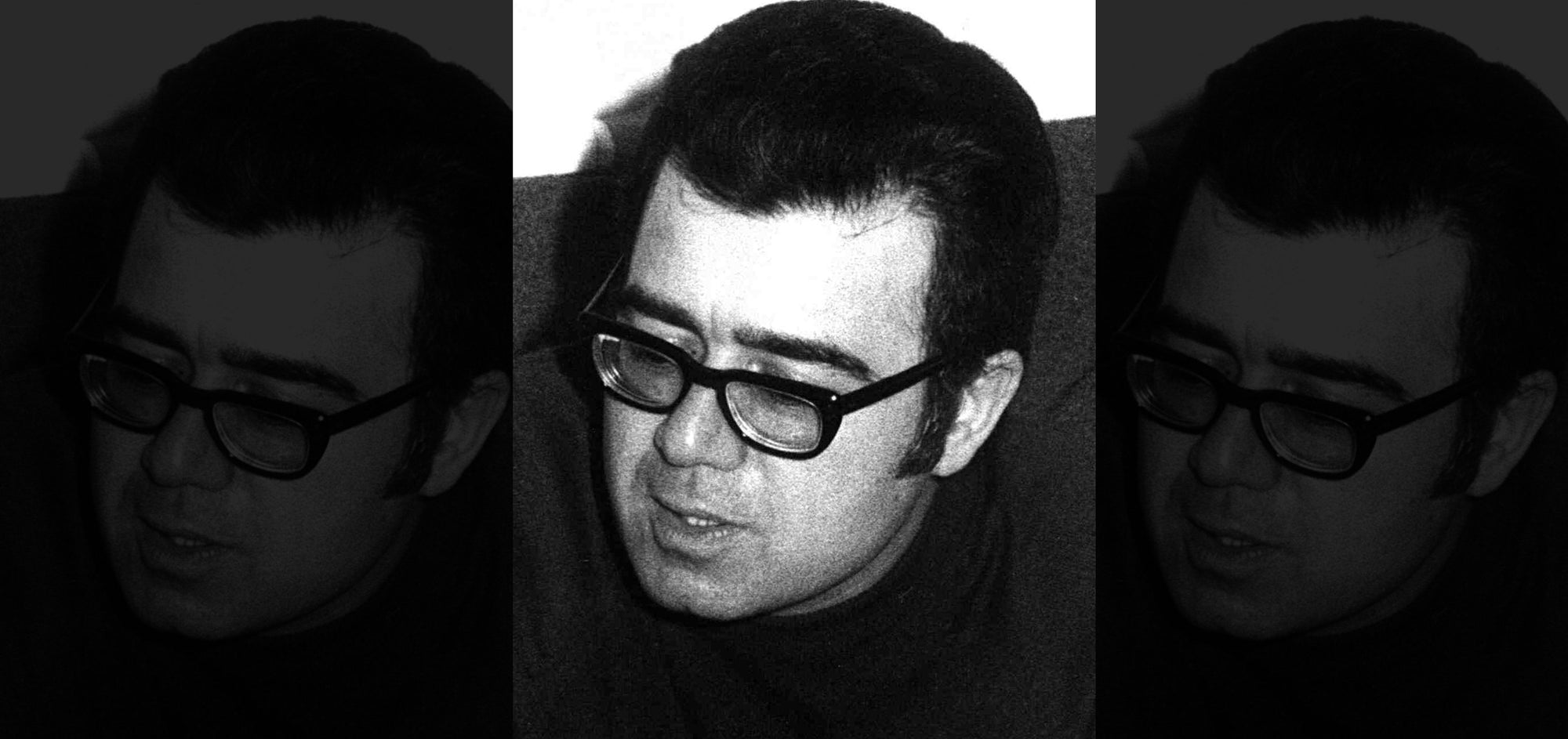

Audiences were intrigued by his “dark and mysterious look,” newspapers wrote about his brooding Armenian eyes that helped him play critically acclaimed roles no one else could. He was the first Armenian-American movie star, a pioneer in playing unusual, eccentric characters sometimes using elaborate makeup that took hours to apply.

But while he was making a name for himself in Hollywood, Carew was considered for a role that would have catapulted him to infinite stardom, one that he ultimately turned down: Dracula.

Just six years after the cult classic brought initial fame to Bela Lugosi, Carew tragically took his own life. Despite a career cut short, his passion for performance never wavered during a career spanning over 50 films.

Like many stories behind the individuals that make up the Armenian diaspora, this one is a mix of ingenuity and accident, born from trauma yet nurtured by the kind of resilience that sometimes last, and sometimes doesn’t.

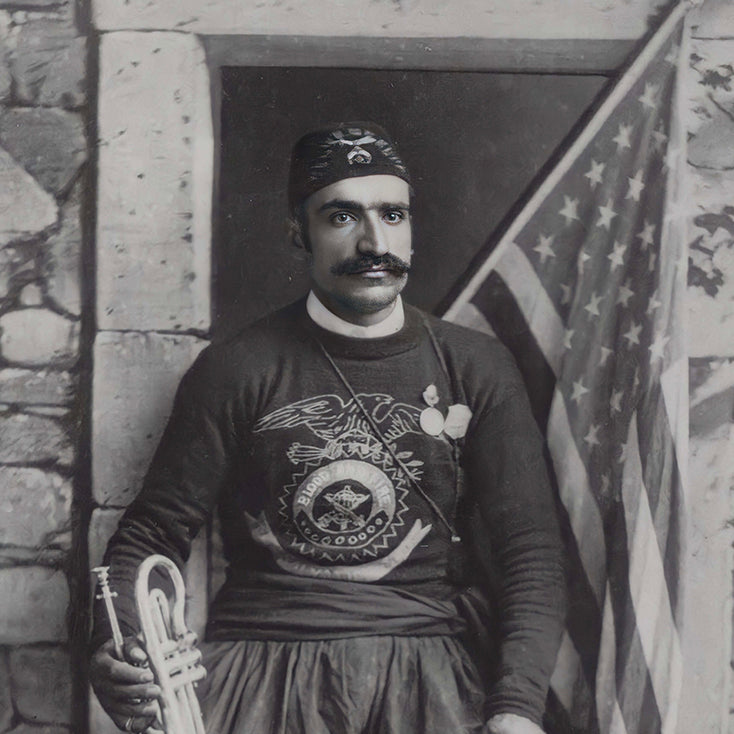

Born Hovsep Hovsepian in 1884 in Trabzon, a city on the Black Sea Coast of the Ottoman Empire, Carew came from a prominent and well-established Armenian family and attended the famous Anatolia College in Merzifon, but his life took a dramatic turn by the time he reached adolescence. His father, who was in the banking business, died when he was just 8-years-old and a few years later, his family was forced to flee during the Hamidian Massacres, which resulted in hundreds of thousands of Armenian and Assyrian deaths - a precursor to the Armenian Genocide beginning in 1915.

While another brother had already escaped to the U.S. a year earlier, Carew arrived in New York City in 1896 with his older brother Ardasches. Their mother joined the Hovsepian brothers by ship a year later.

Carew attended the Cushing Academy in Ashburnham, Massachusetts, a private co-ed boarding school about 60 miles outside of Boston, the Corcoran Art School in Washington D.C., and studied painting. He then enrolled in the Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York City, the oldest acting school in the English-speaking world according to the New York Times.

His talent for the dramatic arts was apparent at a young age - when he graduated in 1904 from the Academy at the age of 20, he won the David Belasco Gold Medal for Dramatic Ability, named after the Jewish-American theatrical producer who had a profound impact on American theatre.

News of the award given to this “Armenian refugee” was covered in a local New York City paper called “The Sun,” perhaps the only documented reference to his real name - Hovsep Hovsepian - in the media. “While the dramatic ability of many Armenian refugees is well known to American Protestant clergyman,” the paper writes, “this is the first formal triumph of the kind.”

While developing his craft on the Broadway stage, Carew married singer Irene Pavloska in 1915, and for a while things were going well. A 1920 edition of the Los Angeles Times called her an “operatic diva” who arranged a surprise for her husband while she was in St. Louis, calling him in Los Angeles so that he could hear her performance over the phone.

They divorced in 1921, but it was during their time together that Hovsep Hovsepian transformed into the critically acclaimed stage and silent film actor known as Arthur Edmund Carew. While married, he became a naturalized citizen, changing his name to Arthur Edmund Carew (sometimes stylized as Carewe). In his naturalization record, his “country of birth or allegiance” is written as “Turkey Armenia.”

Standing at six feet, Carew was very close to the definition of “tall, dark and handsome,” and came to the film industry at a time when few actors looked like him, and the Orientalist fascination with the East in American cinema was in full force, as was discriminatory portrayals of minorities. He quickly developed a reputation for playing the mysterious and sinister roles, becoming a go-to actor for foreign portrayals or whatever cultural views at the time deemed “the other.” The Oakland Tribune called him the “delineator of mysterious, foreign characters on screen.”

In 1923, he played the part of the Svengali in “Trilby,” the film adaptation of the George du Maurier’s 1895 novel about a menacing man who seduces and exploits an English girl (Trilby), making her a famous singer.

The New York Times praised his portrayal.

“It is Arthur Carewe’s revelation of Svengali that dominates this production,” the paper wrote.

Arthur Edmund Carew and Andree Lafayette in the 1923 version of "Trilby."

In The Ten Commandments, he was an Israelite slave and in “The Palace of Darkened Windows”, he played the part of “The Rajah,” a South Asian monarch. He even played the role of a fugitive mix-raced slave in the film adaptation of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

The anti-slavery film was based on the widely popular novel written by Harriet Beecher Stowe, which is said to have been a significant contributing factor to the American Civil War.

Scene from "Uncle Tom’s Cabin", 1927, Universal Pictures

His talent for taking on difficult roles, did not go unnoticed. Whenever a costume picture is being done, newspapers of the time wrote, Carew is mentioned just as naturally and casually in connection with it as Chaplin is with trick derby and baggy pants.

One quality that was more “Hovsepian” than “Carew” that the press picked up on were his eyes, the kind unseen in the West that told a story without ever saying anything.

“Carew is an Armenian,” a columnist wrote in the Des Moines Register in 1926. “So far as I know, he wears his own eyes - do you suppose he could buy or rent such orbs as those?”

Gifs via Tumblr

Other than to comment on his performance, interviews with or about him were rare occurrences in newspapers, though when they did appear, they were memorable and showcased his unwavering devotion to acting.

“Arthur Edmund Carew is a hermit in the most sociable community in the world” The Eugene Guard wrote in 1925. “There’s a reason - not personal, professional. Mr. Carew believes that after a hard day’s work before the camera, no player should permit himself diversion that is alien to his immediate work.”

Five years after women gained the right to vote in the U.S. Carew found himself in a 1925 news item in the Los Angeles Times under the headline “Feminist Convert.”

“Arthur Edmund Carew is at last converted to feminism. Heretofore, he has been a scoffer. Since working in Elinor Glyn’s “The Only Thing,” which Elinor Glyn supervises, he realizes what a tremendous powerful force a woman may play in the social and industrial life of today.

“Madam Glyn has upset all my ideas of feminism,” he’s quoted as saying. “I take off my hat to her as an indefatigable creative worker.”

Carew’s biggest role - the one that he’s most remembered for is from the 1925 film version of “The Phantom of the Opera.”

Staying close to his specialty of portraying foreign characters, he plays the role of “The Persian,” a mysterious man from the Phantom’s past. After the film had wrapped up, Carew was asked to refilm scenes in which his character was changed to a secret inspector named “Ledoux.” Despite the change, Carew’s character (complete with kohl-lined eyes and a wool hat called the Karakul worn by shepherds) remains “The Persian.”

Still from Phantom of the Opera, 1925, Universal Pictures.

It’s no surprise then, that Carew was tapped to play the role of Dracula, one of the most iconic characters of all time.

In 1925, the Quad City Times in Iowa reported that “Arthur Edmund Carew, who plays the mysterious intriguing Persian and who was Svengali in ‘Trilby’ may play the title role.”

Carew, however, turned it down.

Despite other notable actors being in the running after him, the part eventually went to Bela Lugosi, an unknown who intensely campaigned for the role and accepted the meager pay Universal Studios was offering. It’s not clear why Carew opted out, but signs might have pointed to money. Made during the Great Depression Lugosi accepted the low budget film’s salary of $500 (about $7,000 when adjusted for inflation via The Bureau of Labor Statistics) a week, while Carew at the time was making double that (around $1,000 or $14,000 in today’s money).

Arthur Edmund Carewe lies in wait for Glenda Farrell, in the film 'The Mystery Of The Wax Museum' / Warner Brothers.

Continuing his signature eccentric roles, he starred in three notable films - Doctor X, Mystery of the Wax Museum and Charlie Chan’s Secret - before tragedy struck.

In 1936, he had a stroke that paralyzed him from the waist down. Distraught that he would not be able to act again, he checked into a cabin at a campground in Santa Monica, wrote his final say and shot himself in the head. He was 52.

Initially unidentified, news services reported that police found the two notes in the cabin: one to police, asking them not to seek his identity, and the other to the manager of the campground, enclosing $31 ($535 in 2017) “for damage to the cabin.”

His mother, who was critically ill, was never told about what Carew had done.

His brother Garo, who lived in Eagle Rock, a neighborhood in Northeast Los Angeles, was the one who identified him. His remains were cremated and his final resting place was never revealed.

These days, Carew is known among the most dedicated of silent film aficionados but his legacy and innovative contributions to Hollywood have mostly been forgotten. And while Lugosi is still remembered today, things did not go well for the Hungarian-American actor after his breakout role: typecast as a villain, his career declined and he developed a dependency to morphine. He died of a heart attack and was buried in his Dracula cape.

Beyond contributions to American cinema, their stories are a reminder of many things - the pure driving force at the heart of the immigrant narrative, the kind of liveliness only a refugee who has seen so much demise can possess and the complex nature of human beings, who rise and fall, unable to cope with life’s whiplashes and sometimes become overwhelmed by the darkness they came to brilliantly represent.

Story © Ara the Rat. Please do not republish or print or use without prior permission.

52 comments

Meri Grigoryan

Great article! Never heard about Carew. It’s wonderful to know an Armenian connection to silent Hollywood movies. :-)

Great article! Never heard about Carew. It’s wonderful to know an Armenian connection to silent Hollywood movies. :-)

Elizabeth. Kahwati (Kahvedjian)

Fantastic I loved

Fantastic I loved